It isn't strictly about sea level rise, but the current (at the time of writing) cyclone causing havoc in the North Island of New Zealand has prompted this very impassioned speech by James Shaw, co-leader of the Green Party.

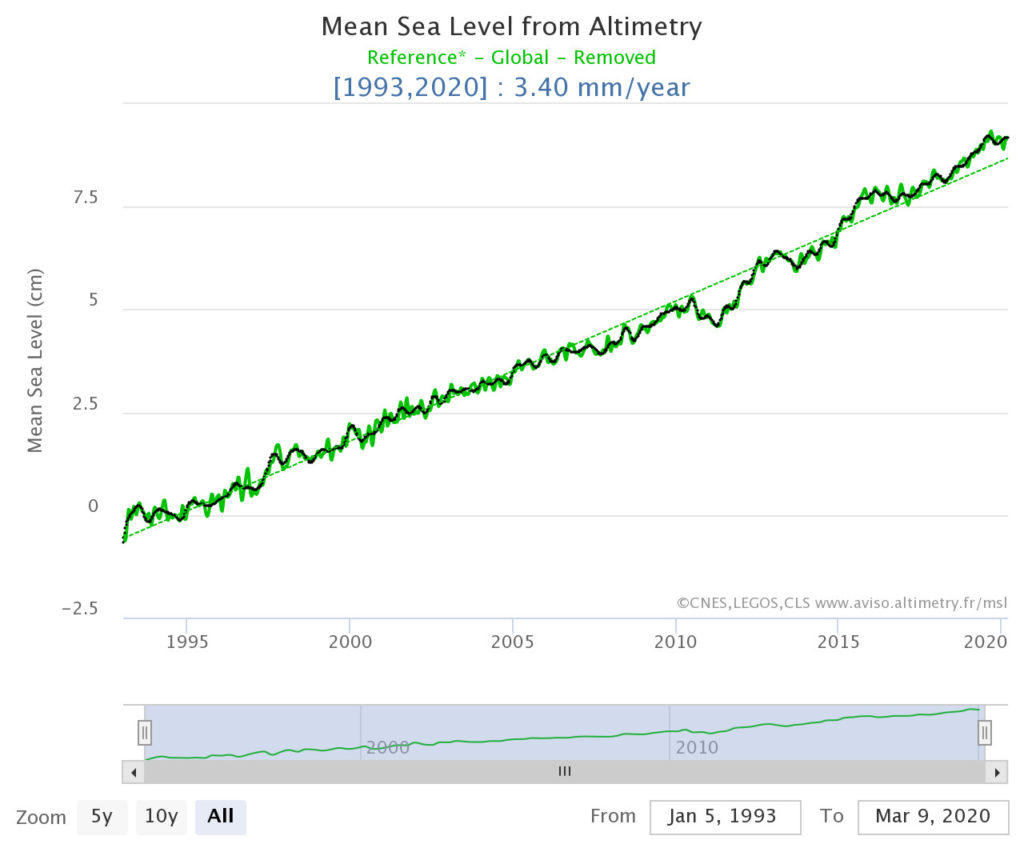

Nasa has just launched a new satellite to measure sea level rise, charmingly named after a recently deceased scientist, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich.

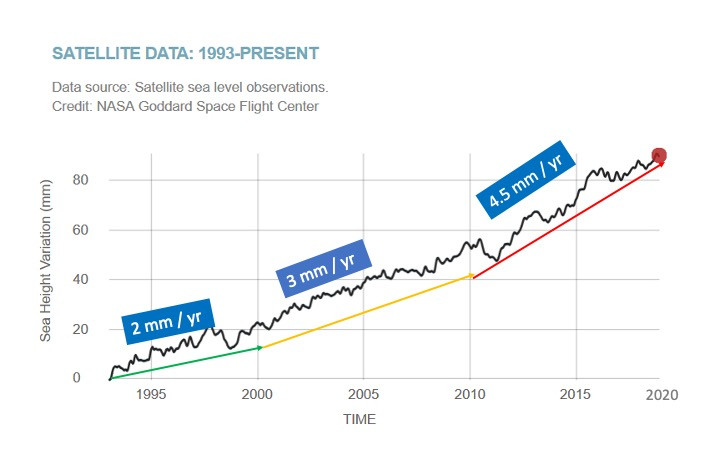

Long story short, here's Nasa's graph of sea level rise as measured by satellites to date:

It's rather a challenge to know how to feel about this.....

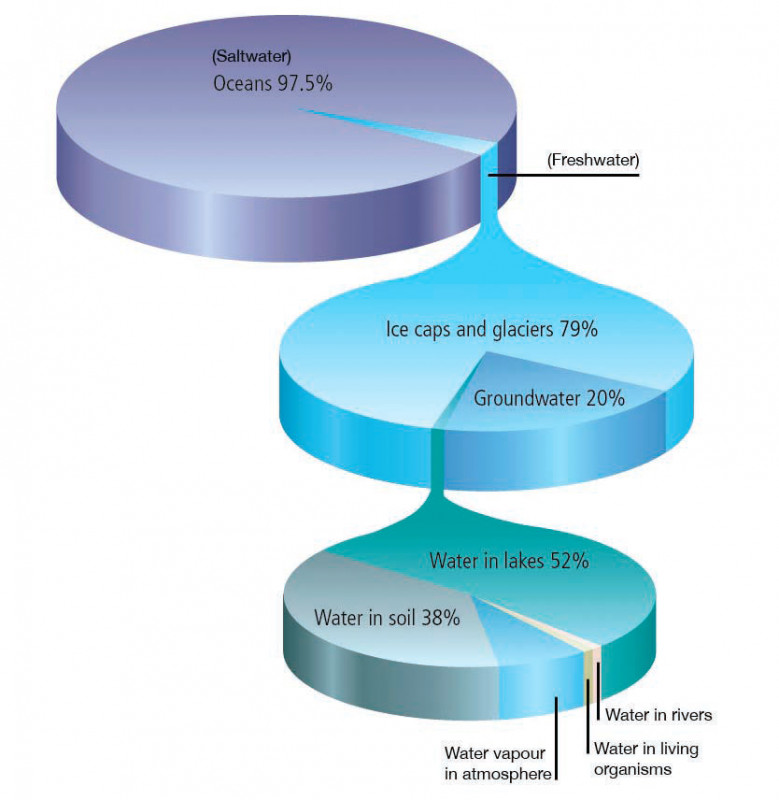

There is not much more to say about this striking graphic from the World Bank.

Managed Retreat - the idea of abandoning sections of coastline that cannot be economically defended in a 'managed' way - is a deeply contentious topic. Like most aspects of climate change it moves at a very slow pace, offering many opportunities to change the subject or sweep it under the carpet.

Politicians are frightened of it, not least because lurking not too far under the surface is the prospect of enormous costs for relocation; so places like Fairbourne are potentially crucial precedents.

The subject has just (July 14 2020) had an airing on the US political website Politico here, accompanied by a deeply - gratuitously? - emotive photo.

Their introduction:

Millions of Americans are about to lose their homes to climate change. In a matter of decades, more than half of the land area of Hoboken, N.J., almost half of Galveston, Texas, and almost two-thirds of Miami Beach, Fla., will become uninhabitable due to sea level rise. The Union of Concerned Scientists warns that up and down the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, more than 300,000 homes worth a combined $117.5 billion are at risk of chronic tidal flooding in the next 30 years. And that’s likely an underestimate: A major report released in June shows that federal flood maps underestimate the number of homes and businesses at risk of flooding by a stunning 67 percent.

And it has been echoed by US sea level guru John England in a blog post here. To quote him:

The U.S. Government is largely silent about “retreat” from the coastline – or at least does not use that word. Retreat has powerful connotations, particularly for property owners. It implies surrender. It carries great economic and political sensitivity. For many coastal communities it poses an existential threat. Nonetheless, managed retreat is increasingly a topic of conversation, as sea level rises, pushing the high water mark ever higher, even in good weather. The worldwide policy problems posed by the need to relocate tens of millions is one the world has never had to confront.

This difficult and emotive subject isn't on any widely visible agenda in the UK at the moment. It should be.

Anyone familiar with flooding in its various forms needs little reminder of the impact this has on lives and livelihoods. The Committee on Climate Change has done its best to shed light on the problem - and the action needed to remedy it - in an extensive report Managing the coast in a changing climate, published in October 2018.

It is a bleak document, for several reasons. One is the subtext, rarely brought to the fore, of the suffering implicit in managed retreat from land and property not defensible on an economic basis. Another is the huge question mark hanging over the Government's ability and willingness to contribute the many billions needed for even a basic strategy to manage the problem.

The document speaks for itself, and is worth reading. However the key findings (not the recommendations) are reproduced below. It is tempting to add emphasis - but which point would not be emphasised?

Climate change will exacerbate the already significant exposure of the English coast to flooding and erosion. The current approach to coastal management in England is unsustainable in the face of climate change:

- Coastal communities, infrastructure and landscapes already face threats from flooding and coastal erosion. These threats will increase in the future. In the future, some coastal communities and infrastructure are likely to be unviable in their current form.

- This problem is not being confronted with the required urgency or openness. Sustainable coastal adaptation is possible and could deliver multiple benefits. However, it requires a long term commitment and proactive steps to inform and facilitate change in social attitudes.

- It is almost certain that England will have to adapt to at least 1m of sea level rise at some point in the future. Some model projections indicate that this will happen within the lifetimes of today's children (i.e. over the next 80 years).

- In England, 520,000 properties (including 370,000 homes) are located in areas with a 0.5% or greater annual risk from coastal flooding and 8,900 properties are located in areas at risk from coastal erosion, not taking into account coastal defences.

- By the 2080s, up to 1.5 million properties (including 1.2 million homes) may be in areas with a 0.5% of greater annual level of flood risk and over 100,000 properties may be at risk from coastal erosion.

- The public do not have clear and accurate information about the coastal erosion risk to which they are exposed, nor how it will change in future.

- Today, coastal management is covered by a complex patchwork of legislation and is carried out by a variety of organisations with different responsibilities.

- The current policy decisions on the long-term future of England's coastline cannot be relied upon as they are non-statutory plans containing unfunded proposals.

- We calculate that implementing the current Shoreline Management Plans to protect the coast would cost £18 - 30 billion, depending on the rate of climate change, and that for 149 - 185 km of England's coastline it will not be cost beneficial to protect or adapt as currently planned by England's coastal authorities.

- To minimise these risks, global emissions of greenhouse gases need to fall dramatically, which would slow sea level rise in the long term. In parallel, the UK needs to strengthen its policies to manage the risks of coastal flooding and erosion.

An older report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation makes the point that coastal communities are already at something of a disadvantage due to a variety of socio-economic and demographic effects. It's a double whammy - relatively poor and vulnerable communities face more extreme burdens from climate change than inland communities do.

Fairbourne, a coastal village in Gwynedd, Wales, exemplifies the legal, organisational, planning and financial challenges of coastal settlements that are too costly to defend.

Opinions will differ on whether or not Fairbourne qualifies for that description. But it is inescapable that as the years and decades pass other places will fall into that category.

There have been good journalistic explorations of the subject; one is in the Guardian of May 18 2019, and another was featured on Channel 4 on Sept 20, 2019:

This is an enormously complex subject. The expected behaviour of ice sheets in response to increased atmospheric temperatures is inevitably imperfectly understood; modelling of future temperatures over Greenland and the Antarctic is also far from perfect; there is huge variability in expected emissions pathways; and much more.

These are all issues far too involved to consider in detail here. For those interested a more in-depth and readable summary of recent research is available from Carbonbrief here, with copious links to the original research.

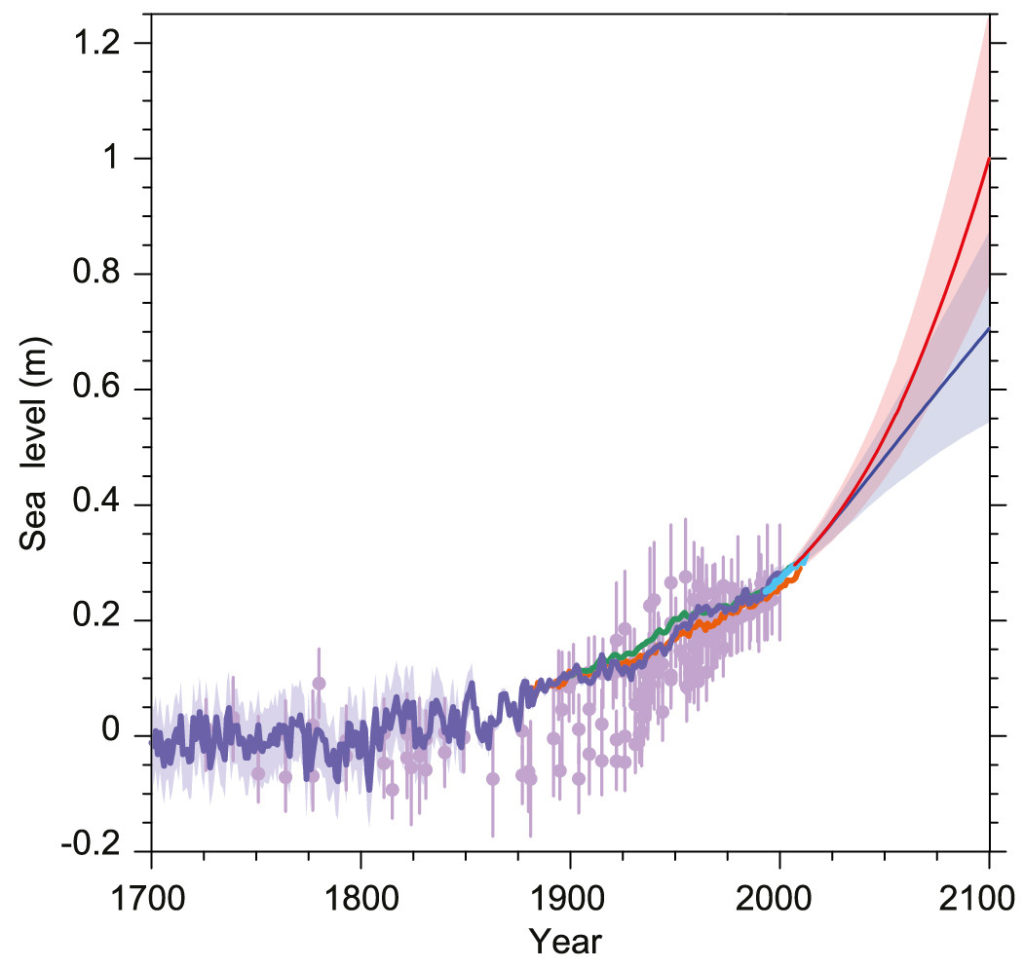

The nearest thing to a gold standard in forecasting is the work of the IPCC, which produces periodic reports updating a comprehensive overview of published science. The most relevant is that of Working Group 1 (WG1) in the Synthesis Report of the 5th Assessment report (AR5) in 2013 – whose summary graph is shown below.

The graph indicates a range of possible rises between about half a meter and over one meter, depending primarily on emissions pathways for the rest of the century. The text of the report states that ‘it is virtually certain that sea level will continue to rise during the 21st century and beyond’.

IPCC publications are the result of a ponderous and somewhat political and therefore conservative process. From their nature they also tend, in cases where research on the subject is fairly fast moving, to be out of date. So it is appropriate to look at alternative sources.

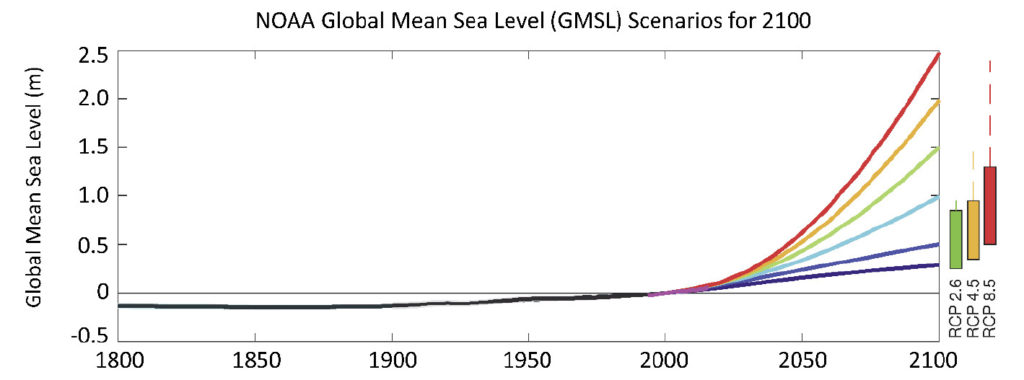

First, a more recent (2017) study by NOAA, the authoritative National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration in the USA. It again takes a scenario approach, with 2100 outcomes ranging up to two and a half meters.

These and many more studies understandably take refuge in scenarios, while acknowledging a certain level of absolutely inevitable sea level rise due to the warming that has already taken place, and the ice-melting and thermal expansion that must inevitably result. Another approach is known as Expert Assessment. Here is Stefan Rahmstorf from the equally authoritative Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), giving a very measured outline of research from PIK in May 2020.

The Carbonbrief review mentioned above takes a variant on the Expert Assessment approach, looking at 'Estimates of sea level rise by 2100 under very-high emissions scenarios, published between 1983 and 2018. Dots represent the best estimate, while bars represent the high and low-end estimates (when available). Black lines indicate IPCC report values, and the grey region extends those values forward until the next IPCC report'. The figure is based on data from Garner et al 2018;

All these studies are very well, but they are not the best possible help for people who want to know what to do - how to think about the future? And what is so magical about 2100 anyway? Why not 2078, or 2136? These dates mostly concern our children, or theirs (or theirs); it's hard to see the difference....

The answer must lie in 'taking a view'. It seems clear that a 1m sea level rise in less than a century is very possible; 2 meters is far from being out of the question. For its part, the Environment Agency has taken a bold stance: As a nation, we need to be prepared for a 2°C rise in global temperatures, but plan for a 4°C rise , which would undoubtedly lead to more than 1 meter rise. It remains to be seen whether it will have the funding to match that ambition.

And the crux of the issue is the impact; what are the implications for people living on the UK coast? Our current best shot at exploring this is here.

Sea level is rising.

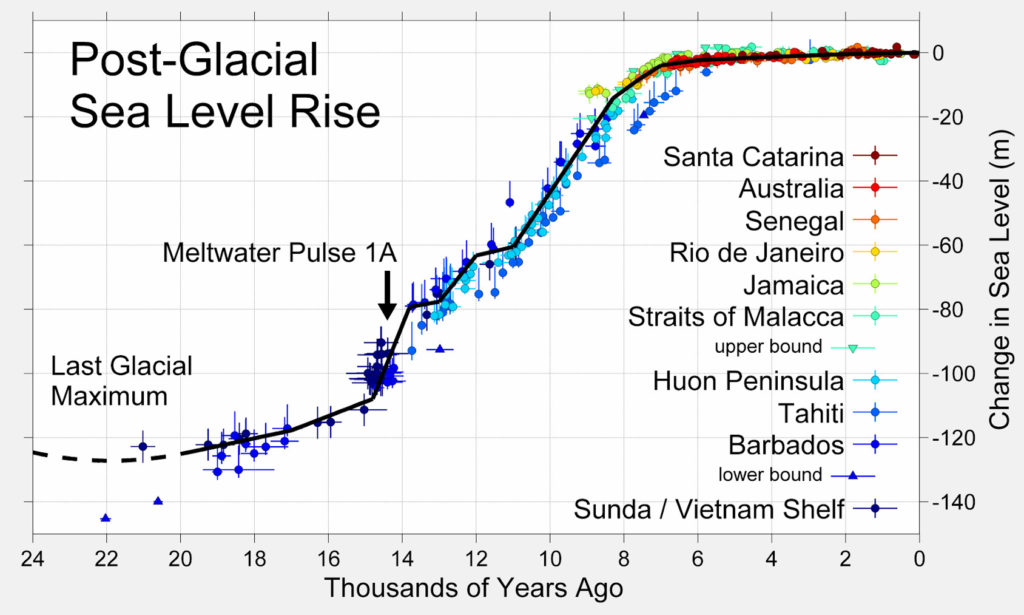

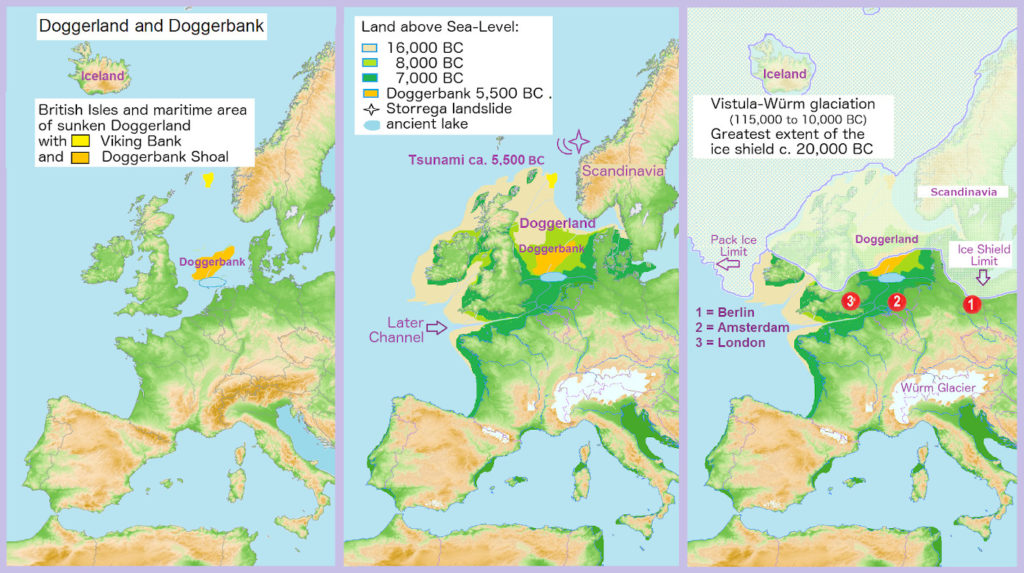

First of all, the context. Since the last ice age maximum (about 20,000 years ago) the sea has risen by about 100 meters, as ice sheets and glaciers world-wide melted. But for about the last 7,000 years the level has been pretty stable.

This is illustrated in more local history: at the time of the last ice age Doggerland was a huge area between Britain and Denmark; as the ice retreated and the sea level rose, it shrank, forming a marshy land round the perimeter of the Low Countries and the East coast of the UK.

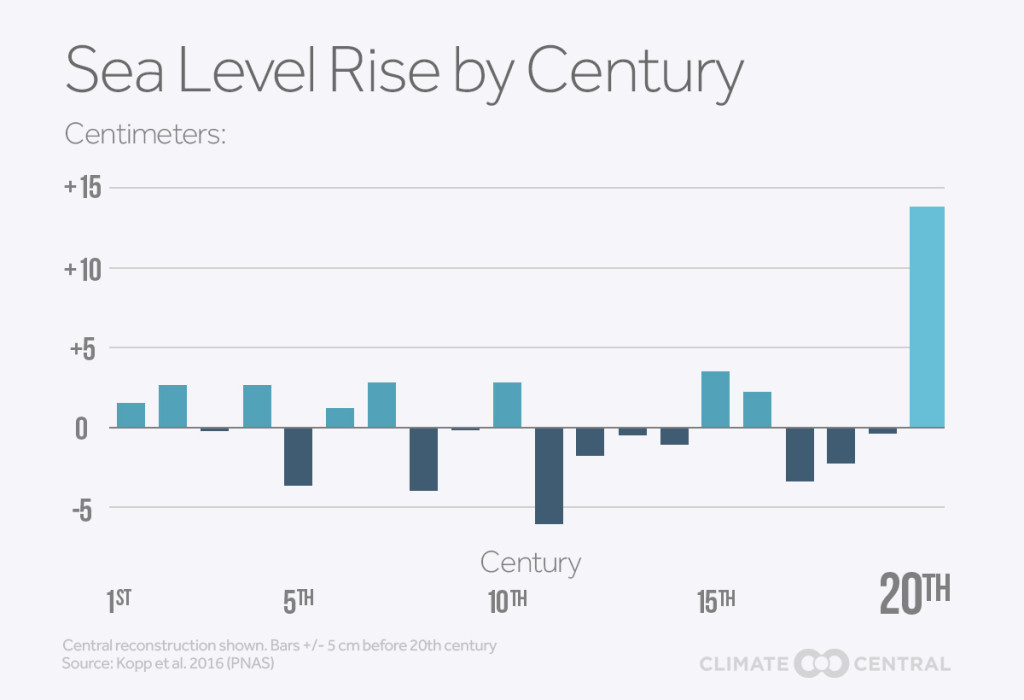

Which brings us to recent times. Careful analysis of a variety of records demonstrates that over a couple of milennia of modest changes in sea level - upwards and downwards - the 20th century has seen the vast majority of rise in that period.

It is virtually without doubt that this has been caused by the burning of fossil fuels. The CO2 emissions from this has caused warming of the atmosphere (due to the 'enhanced greenhouse effect') and in turn sea level rise, for two main reasons:

- The melting of ice sheets and glaciers, especially in Greenland and Antarctica.

- The warming of the sea as it absorbs increased heat from the atmosphere, causing it to expand slightly.

The result is a rise in mean global sea levels currently of about 3.4 mm per year. There are variations from place to place due to the wind, localised warming effects, and local melting of ice.

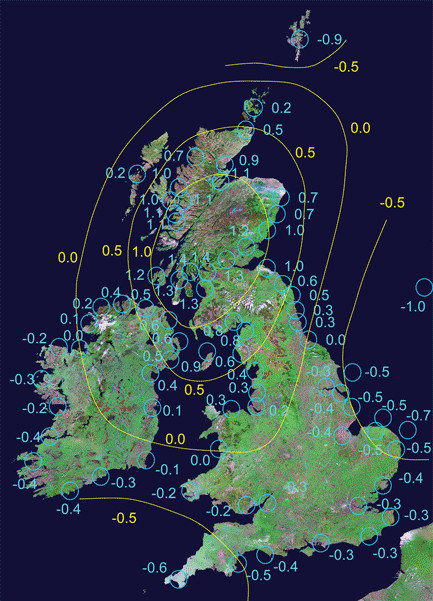

To complicate matters, there is another factor going on – adjustment of land levels following the removal of the ice mass 7,000 years ago. This map shows that Southern Ireland and Wales, and Southern and Eastern England are continuing to sink, whilst Scotland is rising, at rates less than previously predicted. This effect, in the region of 1mm per annum is, however, not as pronounced as sea level rise.

The short version is therefore that the sea level is currently rising round the UK coast at about 3 or 4 mm a year, i.e. 30 cm (roughly a foot) a century. There is every reason to believe that this rate will accelerate, however, as covered in our post on Forecasting Future Sea Levels. And even more to the point, we start to explore here what the impact of this is likely to be on the coast.